Lesson 11: The Collapse of the Weimar Republic and Hyperinflation

The Weimar Republic, formed in Germany after World War I, faced an economic crisis that was, in many ways, the precursor to the catastrophic hyperinflation that engulfed the country in the early 1920s. After the war, Germany was burdened with severe reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, which demanded that the country pay vast sums of money to the Allies. In an attempt to meet these obligations, the German government began printing money at an unsustainable rate. The consequences of this decision became apparent as the value of the Reichsmark, Germany’s currency, plummeted, triggering a period of extreme inflation.

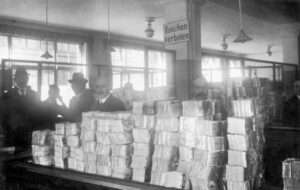

By 1923, inflation reached astronomical levels. Prices for everyday goods skyrocketed, and the currency became essentially worthless. The cost of a loaf of bread, which had been just a few marks in 1919, rose to trillions of marks by the height of the crisis. The German government continued to print more money, unable or unwilling to stop the inflationary spiral. People began to use wheelbarrows full of banknotes to buy basic necessities, and the middle class saw their life savings vanish overnight. The rapid depreciation of the Reichsmark led to a loss of confidence in the currency, and a shift toward bartering and the use of foreign currencies.

The root cause of the hyperinflation in Weimar Germany can be traced back to the financial strain caused by the war reparations and the government’s response to them. Germany had already been economically devastated by the war, with widespread destruction of infrastructure, loss of human capital, and diminished industrial output. The reparations, which required the payment of billions of marks to the Allied powers, placed an unbearable burden on the country’s finances. Instead of finding ways to restructure the economy or negotiate a reduction in the reparations, the German government resorted to printing vast amounts of money to cover its obligations. This desperate act, while temporarily alleviating immediate financial pressures, led to the destruction of the currency’s value.

As the government continued to print more money, confidence in the Reichsmark eroded. The inflationary cycle became self-perpetuating, as people expected prices to keep rising and sought to spend their money as quickly as possible. This led to an acceleration of inflation, where the more money the government printed, the faster prices rose, and the less value the currency retained. The collapse of the Reichsmark was a stark reminder of the dangers of relying on inflationary measures to solve deep-seated economic problems.

The impact of hyperinflation on the German population was profound. The middle class, which had once enjoyed relative prosperity, was hit hardest. Many had invested their savings in bank accounts or government bonds, only to see those assets rendered worthless. As the purchasing power of the Reichsmark crumbled, citizens found themselves unable to afford even basic necessities. Social unrest spread as families struggled to feed themselves, and the sense of national humiliation and economic hopelessness intensified. The gap between the rich and poor widened, with the wealthy able to protect their wealth by converting it into tangible assets or foreign currencies.

Politically, the hyperinflation crisis eroded confidence in the Weimar Republic and its government. The inability to control inflation led to a loss of faith in democratic institutions, paving the way for extremist movements to gain traction. The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, which capitalized on the disillusionment and frustration of the German people, was one of the most significant political consequences of the hyperinflation crisis. By the time the hyperinflationary period ended in 1924, the Weimar Republic had lost much of its legitimacy, and the country was on the path toward further political and economic turmoil.