Lesson 12: The Zimbabwean Hyperinflation Crisis

Zimbabwe’s descent into hyperinflation, which reached an eye-watering 89.7 zillion percent per month in 2008, was the result of a complex interplay of political and economic factors. One of the primary catalysts was the government’s land reform policies, which saw the forced seizure of commercial farms from white farmers in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This led to a dramatic collapse in agricultural production, which had been the backbone of Zimbabwe’s economy. The country’s once-thriving farming sector, which had been a major exporter of tobacco, maize, and other crops, was devastated by the loss of expertise, capital, and infrastructure.

As agricultural output plummeted, Zimbabwe’s economy suffered from widespread food shortages and declining export revenues. To cope with the crisis, the government, led by President Robert Mugabe, began printing money to cover its growing budget deficits. The central bank, under the leadership of Gideon Gono, printed increasingly larger amounts of currency, which only worsened the inflationary spiral. In an environment where there was little production to support the money supply, the value of the Zimbabwean dollar rapidly eroded. By 2008, the country was experiencing the worst hyperinflation in recorded history.

The Zimbabwean government’s decision to print vast amounts of money in response to its economic woes led to a disastrous spiral of hyperinflation. Initially, the government printed money to finance its land reforms, cover external debt, and meet domestic spending demands. However, the money printing was done without any regard for economic fundamentals or the production of goods and services to back the increased money supply. As more money flooded the economy, the value of the Zimbabwean dollar continued to fall, and prices soared uncontrollably. Inflation became so extreme that it was measured in astronomical numbers, with prices doubling every few hours at the peak of the crisis.

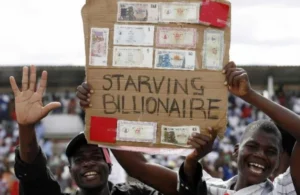

The lack of confidence in the currency led to a massive collapse of the formal economy. People turned to barter, trading goods and services directly instead of using the devalued currency. Foreign currencies, particularly the US dollar, became the preferred medium of exchange, and the economy became dollarized. The government’s response to the crisis, which included printing even more money and introducing increasingly larger denominations of banknotes, only fueled the cycle of hyperinflation. In 2008, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe issued a 100 trillion Zimbabwean dollar note, a symbolic but futile attempt to address the collapse of the currency.

The consequences of hyperinflation in Zimbabwe were devastating for society. The most obvious impact was the destruction of personal savings. Zimbabweans who had worked hard to accumulate wealth found their life savings wiped out as the value of the currency disintegrated. Pensions, bank accounts, and savings were all rendered meaningless, and the middle class, which had once been the foundation of Zimbabwe’s society, was decimated.

As the economy collapsed, social systems also began to break down. Healthcare, education, and other public services were severely affected by the lack of resources. The government’s ability to provide basic services was compromised by the hyperinflationary environment, and the population’s standard of living deteriorated rapidly. The social fabric of the nation was strained as unemployment reached astronomical levels, and many people were forced to leave the country in search of work. Economic migration became widespread, with millions of Zimbabweans fleeing to neighboring countries like South Africa, further exacerbating the country’s problems.

The hyperinflation crisis in Zimbabwe was not only an economic catastrophe but also a political one. The government, led by Robert Mugabe, was increasingly unable to address the country’s economic decline, and the loss of confidence in the currency reflected a broader loss of trust in the political system. The government’s efforts to suppress dissent through violence and intimidation only worsened the situation, leading to widespread unrest and a breakdown of law and order.

The economic collapse also weakened the government’s ability to maintain control over the country. While the ruling ZANU-PF party continued to hold power, the legitimacy of the government was increasingly called into question, both domestically and internationally. The economic hardships experienced by ordinary Zimbabweans, coupled with the growing influence of opposition groups, ultimately led to the downfall of Mugabe’s regime. The economic collapse created an environment in which political instability, social unrest, and widespread poverty became the norm, contributing to Zimbabwe’s ongoing struggles.