- Home

- All Courses

- For Beginners

- A Brief History of Money and Inflation

Curriculum

- 6 Sections

- 20 Lessons

- Lifetime

- Section 1: Money and Its Role in SocietyThis section explores the foundational role of money in society, examining its purpose, early forms, and the development of banking systems that led to the creation of paper money.3

- Section 2: The Rise of Gold as MoneyTrace the rise of gold as a symbol of value, from the classical gold standard to its eventual decline, exploring how gold-backed currency shaped economies for centuries.3

- Section 3: Fiat Money and the Birth of InflationThis section delves into the transition from tangible-backed currency to fiat money, explaining how the ability to print money without limits gave rise to inflation and its societal consequences.3

- Section 4: Historical Case Studies of Civilizations Falling Due to Soft MoneyHistorical instances where empires and nations fell due to the mismanagement of money, from ancient Rome to modern-day Zimbabwe and Venezuela, highlighting the dangers of inflation and currency collapse.5

- Section 5: Modern Monetary Systems and the Consequences of Fiat MoneyHow modern economies operate within fiat systems, focusing on the role of central banks, the inflationary cycle, and the effects of rising inflation on individuals and society.3

- Section 6: The Future of Money Beyond FiatThe final section looks to the future, discussing the dangers of continuing on the fiat path, the lessons we can learn from history, and the case for returning to sound money principles to safeguard future economic stability.3

Lesson 14: The Rise and Fall of Yap’s Limestone Currency

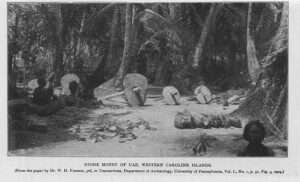

The Yapese people, from the small island of Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia, had an interesting and unique form of currency that is often cited as an example of how money can evolve from scarcity and utility. They used large limestone discs, known as rai stones, which were integral to their social and economic life. These stones were not merely items for trade; they carried a deep cultural and historical significance, embodying the community’s values of effort, rarity, and communal acknowledgment.

Rai stones were not just any stones; they were carefully crafted from limestone found on other islands, far away from Yap itself. The process of creating a rai stone was arduous and time-consuming. The limestone had to be quarried by hand from quarries located on the island of Palau, some 400 miles away. Once the stone was quarried, it was then transported by canoe, often on perilous journeys across the open ocean. The stones varied in size, with some being as large as 12 feet in diameter, though many were smaller and more manageable. The larger stones were considered more valuable, but all were tied to a social contract among the Yapese people.

What made these rai stones particularly unique was their form of ownership. While the stones themselves were physical objects, their value wasn’t necessarily tied to their mobility. Larger stones, which were often too big to be moved, would remain on their original location, while ownership would be transferred via oral agreements and public acknowledgment. The transfer of a rai stone was often announced in a ceremony, where the people in the community would witness and recognize the new ownership of the stone. This system relied heavily on social consensus, trust, and reputation, all of which reinforced the currency’s value.

Because rai stones were so labor-intensive to create and transport, they were inherently scarce. This scarcity was a key factor in their acceptance as a form of money. The Yapese, like many ancient societies, understood the value of rare resources and saw the effort involved in acquiring the stones as a reflection of their worth. The larger and rarer the stone, the more valuable it was considered, and the more prestigious the transaction. Rai stones became a medium for settling significant debts, paying for land, and even arranging marriages. The value of these stones was deeply embedded in the society’s customs, and the stones themselves became a form of social capital.

However, the arrival of Europeans on the island in the 19th century marked a turning point for the Yapese monetary system. The European colonizers brought with them new rai stones, which were easier to produce and didn’t carry the same societal weight as the stones crafted from Palau’s limestone. These new stones were sometimes made from locally available materials, making them far more accessible and less scarce. This influx of foreign stones began to erode the value of the rai stones, as the core principle of scarcity, which had underpinned the Yapese monetary system, was undermined.

As more stones were introduced into the community, the scarcity that had made the rai stones valuable diminished. The Yapese people soon found that these new stones didn’t have the same historical and cultural significance as the traditional rai stones from Palau. The society’s reliance on the original rai stones for important transactions began to break down, as people could now use the easier-to-make stones in place of the rarer ones. The value of the rai stone system, which had been so central to Yapese society, began to deflate.

This story of the Yapese is a powerful example of how inflation and currency debasement can occur in any system. Just as the Yapese people’s currency system suffered when the supply of rai stones increased, fiat currencies experience similar devaluation when governments print more money. In both cases, the core principle of money—scarcity—is disrupted, and the value of the currency is diminished. The Yapese experience underscores the danger of overexpansion in any monetary system and highlights the importance of scarcity in maintaining the value of currency.

The Yapese were not unique in their use of a commodity-based currency. Other cultures and civilizations throughout history have relied on different forms of money, such as shells, salt, and even cattle. However, the Yapese story stands out because it illustrates how a currency based on scarcity can be upended by the introduction of an easier, more accessible version of the same currency. It’s a cautionary tale about how money must be backed by something that is difficult to replicate if it is to retain its value.

The tale of the Yapese shows the critical role that trust and social consensus play in the value of money. The rai stones were not just objects; they were symbols of the community’s collective trust in the value of the stones and the reputation of the people involved in the transactions. The transfer of a rai stone was not just a financial transaction—it was a public event that involved social recognition. This element of trust and societal agreement is essential to any monetary system, whether it involves stones, paper money, or digital currency.

In many ways, the collapse of the Yapese monetary system parallels what has happened in modern economies. When money is debased, whether through the introduction of new rai stones or the printing of more fiat currency, the trust in the currency erodes. People begin to lose confidence in the money, and it can no longer function as a reliable store of value or medium of exchange. This erosion of trust is at the heart of inflationary crises, from ancient civilizations to modern economies.

The story of the Yapese also offers a valuable insight into the importance of maintaining a sound monetary system. Just as the Yapese currency system faltered with the introduction of new stones, modern economies must safeguard against the devaluation of their currency through irresponsible monetary policies. By ensuring that money remains scarce, difficult to counterfeit, and widely trusted, societies can avoid the pitfalls of inflation and currency collapse that have plagued so many civilizations throughout history. The Yapese people’s experience serves as a timeless reminder of the fundamental principles that underpin any successful monetary system.

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Cookie Preferences

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: business.safety.google